Bad New Things, Good Old Things (and maybe some Good New Things…) ep.7

The sun is back!

The left is debating identity politics again! The Trumpian moral panic over ‘wokeness’ and Diversity, Equity and Inclusion training, and the rollout of leftwing journalist Ash Sarkar’s debut book, Minority Rule: Adventures in the Culture War, have coalesced to create an uneasy feeling within sections of the movement. The stories of salad spinner rows and Roger Hallam sparking moral outrage, depicting an uncomfortable image of the left’s intolerance for debate and tolerance for destructive forms of identitarianism, have riled some comrades up.

The reaction goes: these examples of cultural isolationism are minoritarian episodes, largely unindicative of the broader left, slight in importance compared to the cultural identity politics of the far right, and as Shanice McBean has argued, not talking points the left should entertain in the middle of a cross-Atlantic moral panic mobilised to repress the energies behind the mass social movements of this decade.

Sarkar’s argument that the right has become adept at wielding moral panics against social minorities in the service of elite minority rule, reproducing languages and cultures of grievance honed on the left appears compelling. That it chimes with a generation of activist critique from Ambalavaner Sivanandan and the Combahee River Collective, to Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor should perhaps encourage us that this isn’t simply a foil for rightwing talking points.

We may quibble with how communist interlocutors redress attempts to paint leftwing subcultures in the media, but I’m going to refrain from any substantive comment on the book until I get around to reading it. Ultimately, I suspect there’s a great deal more commonality between Sarkar and her leftwing critics than the spiralling debate based on brief, online video reels has allowed. There is one point I want to make though which I think all the online discussion has tended to miss. In a contribution largely geared towards rendering the problems of liberal identity politics, Richard Seymour has asked: “What would a viable anti-identity politics look like?”

I think this question, asked by large quarters of the left, is the wrong way around. Socialist politics should absolutely avoid the tendency to do ‘identity-work’ when it invokes essentialism and sacralisation, but we cannot avoid the reality that people’s understanding of the world and how they relate to one another is increasingly mediated by the raw materials of culture, scraped together unevenly to cultivate one’s sense of self. This glaring question, of one’s subjectivity, is something that the right is becoming rapidly successful at shaping and cohering in a way that I do not think our side can claim to. There is the murky world of politics and the often frustrating world of organising and when we step into both, I think we desperately need to suss out practically how our interventions can chime with and facilitate the flourishing of forms of culture and identity conducive to a socialist politics of freedom dreams.

Stuart Hall, in a wonderful late eighties essay on post-Fordism argues, like an earlier Marx, that we need to have one foot in the new, and one foot out of it. We cannot simply resist contemporaneity. Modernity contained the wonders of cinema, architecture, music and the aspirations of mass movements for human liberation, side-by-side with the horrors of mass industrialised violence against ‘the wretched of the earth’. What we nebulously call post-modernity saw working class kids like me relish in the passions of grime at the same time as the power structures imbibed within us a depressive melancholia prohibiting the possibility of a liberated future. I’m increasingly of the opinion that the left and the labour movement cannot avoid the tough process of ‘identity-work’. The organising we do, the spaces we build for discussing ideas, strategising and creating a new socialist culture will produce new social agents crafting their own identities in the course of the struggle. This is the unavoidable work of subjectivation and as the liberal identitarianism of the political centre hollows out, the left must be prepared to facilitate radical subjectivities which can repel the rise of the far right.

Early last month, I was taken aback by a film I had been meaning to watch for a while. Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru follows a low-level Tokyo state functionary whose dull and ordinary life is interrupted by a cancer diagnosis giving him six months to live. On the precipice of death, Kanji Watanabe finally sees life. The film’s opening scene, of a group of furious mothers demanding that a cesspool in their area be drained so that a playground can be built for their children, becomes the protagonist’s final mission. A rendition of Tolstoy’s Ivan Ilyich, the first half sees the bureaucrat’s perplexed anxiousness transform into an uneasy embrace of life’s unknown, drinking booze, making a new, younger friend and enjoying the finer things the world has to offer. The film’s second half takes place at his funeral, as his former colleagues try to piece together his last days, pondering how much he knew about his illness, confused by his determination to get the children’s playground built. One of the picture’s most powerful scenes, of the teary-eyed mothers paying respects to the dead bureaucrat captures the film’s spirit: Kanji, initially seeing these women as pests, realises once a deadline is imposed upon his life, that these are the people he should serve. Against gangsters, real estate developers and the Kafkaesque nature of postwar Japan’s ballooning state bureaucracy, our Public Liasion chief creates a space for children to realise the Good Life he was always too inundated to embrace. He gets his moment though, in the closing scenes, singing and playing on the newly-built park swings. It’s not my favourite Kurosawa film, but it’s a masterpiece nonetheless, and regular collaborator Takashi Shimura pulls off a wonderfully melodramatic performance.

Thanks to a dear friend, my life has been enriched by following Zohran Mamdani’s bid for the New York mayoralty. The son of renowned thinker Mahmood Mamdani and famous filmmaker Mira Nair, this socialist is spearheading a Democratic Primary campaign to oust corrupt mayor Eric Adams. A stroke of communications genius, I urge everyone to watch his video on ‘Halalflation’. Taking popular fast foods like doner, shawarma and gyros, identifying how state legislation impoverishes small business owners and working class consumers alike, Mamdani’s message brings the two cohorts together in a love of affordable foreign food and hostility towards municipal elites. He has an illuminating appearance on Chapo Trap House in which he expands upon his commitment to rent controls, universal childcare, free buses, de-carceralisation and - a novel idea among the political left - publicly-owned grocers selling low-cost food. It is rare to see a campaign that fuses bread-and-butter demands with abolitionist impulses and solutions to climate-flation, leaning into a version of universalism and left futurity. Whilst the corrupt Democrat tycoon and former New York state governor Andrew Cuomo is way ahead in the polls, Mamdani is now best placed to challenge him. This is one to watch and learn from in more ways than one!

Dripping in class and serenity, the Altons’ Heartache in Room 14 is unquestionably my album of the month. Self-described as indie-soul retro, this band of South East Angelenos, fronted by the piercing, syncretic voices of Adriana Flores and Bryan Ponce, are the perfect way to welcome the Spring and enjoy the sun. As wonderful as it is, I wouldn’t start with this album though. Their previous project, In the Meantime, became one of my favourite projects of all time last year, leaving you with tones of B.B. King, the Clash and even, dare I say it, an early Kings of Leon flex.

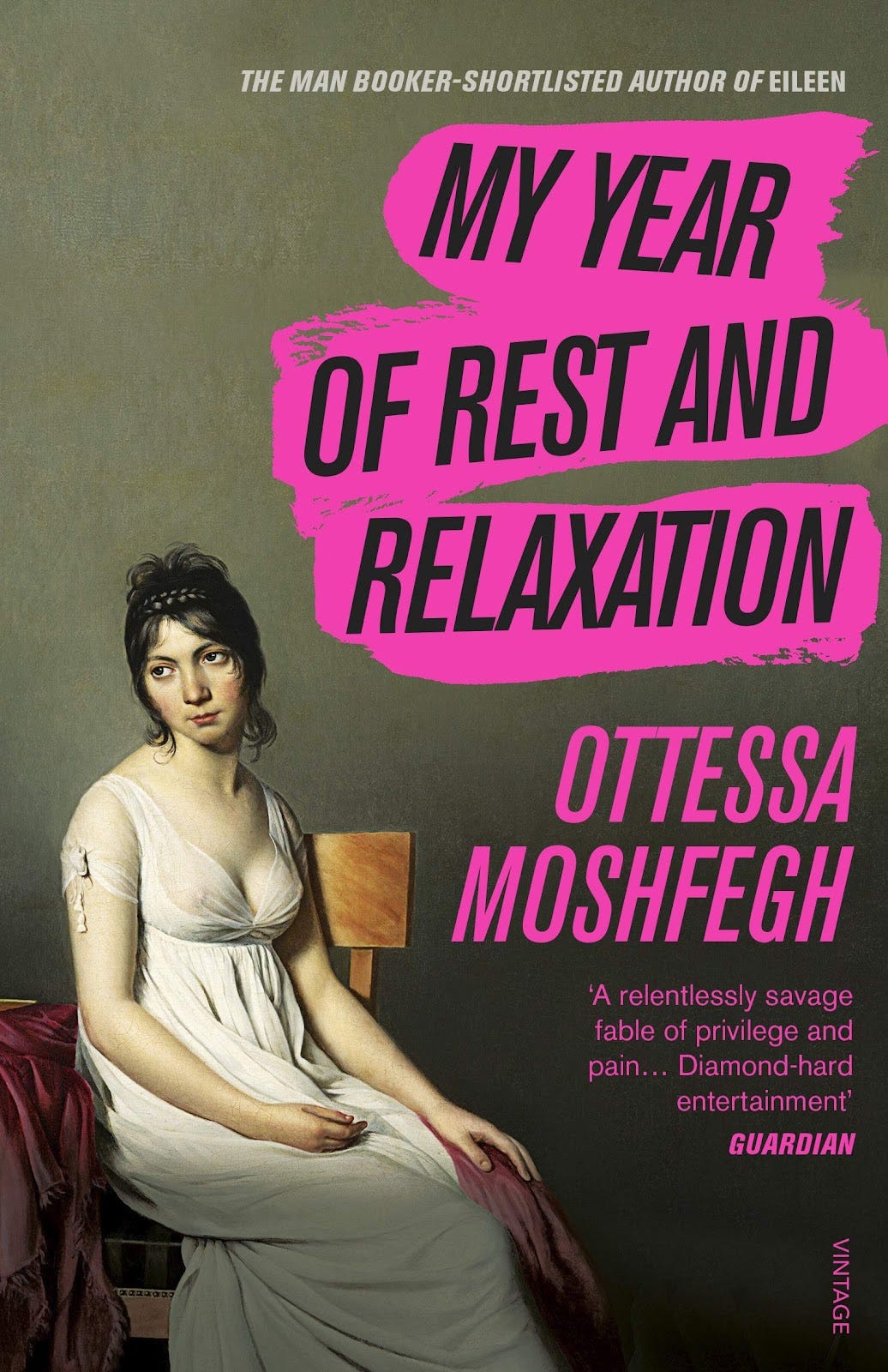

One of the biggest challenges I have had while writing the book I am working on is just how little time it has left me to read fiction. For well over two years, I’ve been drenched in academic and non-fiction research and it’s made the joy of reading substantially more sterile than I would have liked. That all changed last month when I picked up my first novel in 27 months, recommended to me by my wife. Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation is a brutally funny and moving story of one woman’s attempt to use the latest pharmaceutical innovations to sleep for a year, escaping the traumas of the past and the gendered expectations of the present. Set at the turn of the century, it feels like a far more contemporary tale, one that reckons with how psychically and socially disabling capitalist society can be, even among its more fortunate citizens. I just could not put it down.

On Friday evening, some friends and I went to the book launch of the lovely Sam Wetherell’s Liverpool and the Unmaking of Britain (a title you should be as excited to read as I am). It was an event that captured the spirit of the book, the questions it sought to provoke and engage with, whilst enticing long-standing citizens and organisers in the city to grapple with its themes. Leaving the event, we discussed the book’s contents throughout the evening, over drinks and food, delighted we could be there, but agreeing that we would simply have loved to hear more from both Sam and the room. We simply do not have enough spaces in our movement where we can discuss ideas, histories, strategies and principles, shorn from the largely toxic cultures of the attention economy, and it’s an issue. One of the projects I have been most proud to have been involved in over the past few months is this coming summer’s Festival of the Oppressed, hosted and organised by revolutionary socialism in the 21st century. An attempt to work through how we “reignite popular agency, build new solidarities, and imagine future alternatives” in a dark world, this will be a weekend of spirited discussion and concerted investigation as we discuss how capitalism produces and remakes oppression: gendered, racialised, sexual, classed, and colonial. There will be opportunities for fun, dancing and art too. Sign up if you are interested!

I’ll leave you all with the brilliant New Jazz Underground and their rendition of some classic Kendrick Lamar B-sides. Putting the lyrics of Drake’s ‘Passionfruit’ to the beat of K Dot’s devastating ‘Meet the Grahams’ is as cool as it is cruel.